While I can’t say 2011 was a banner year for cinema, especially considering how phenomenal of a year 2010 was, I will admit I saw a decent amount of great films and enough interesting films to round out a pretty good top ten list. During the start of the year I wasn’t too pleased with any of the new films the year had to offer but was happy to see some of my favorite films from 2010 get US theatrical releases. The second half was a little better but only because I had all of December to focus on finding and watching good films. Once I sorted through the many duds, I actually found myself having to make tough decisions on which films weren’t gonna be in my final ten. Sadly these were the ones that failed to make the cut:

The Future – dir. Miranda July (United States/Germany)

This was a film that got it’s share of criticism, much of which I didn’t understand. Sure there are moments where the film may feel cloying at some points with it’s quirkiness (a talking cat, new age hipster lifestyle, stopping time) and the character do often come off as narcissistic, but the film, and July, are aware of all this and even agrees. The film’s strengths are in the ways it’s able to shift from quirkiness to sadness. Though it may look like just another cheap Wes Anderson rip-off with mumblecore sensibilities, The Future is actually able to balance it’s whimsy with a genuine feeling of heartbreak. Richard Brody compared Miranda July with Marguerite Duras when he wrote about the film (he even listed it number 1 for the year). It’s an interesting comparison and worth noting that July is no afraid to bring a very literary aspect to work or let it go into darker and more psychological areas.

Kill List – dir. Ben Wheatley (UK)

Audacious isn’t a strong enough word to describe this film. Wheatley’s Kill List may be the hands down most interesting film I’ve saw in 2011. This isn’t to say its a particular good film, but it’s one that is nevertheless thought provoking. Combining aspects of occult horror and gritty kitchen sink drama to a story about two hit-men, Wheatley turns what could have been another routine exploitation film into a fascinating and violent allegory for Post-Blair England. This is a chilling film and one that I suspect to be a cult hit in a few years.

The Innkeepers – dir. Ti West (US)

Ti West is the most exciting filmmaker working in the horror genre today and his follow up to his cult hit House of the Devil proves it. Doing his own version of the haunted house story, taking place during the final days of The Yankee Pedlar Inn where the employees take on the persona of “ghost catchers,” West once again shows that the importance of a good horror film relies more on atmosphere than on nonsensical violence. Its my pick for the year’s best horror film and one I’m afraid may be get overlooked.Be sure it doesn’t.

Crazy Horse – dir. Frederick Wiseman (France/US)

It’s pretty incredible to think Wismen has been working since the 60s. While I believe Crazy Horse may not rank among his greatest works, its still a worth watching. Using his verité style, Wiseman chronicles the legendary Parisian cabaret club,Crazy Horse. The film does run a little too long but the dance routines are pretty spectacular and beautifully shot.

Okay now for the the ten:

10. The Kid with a Bike/Le gamin au vélo – dir. Jean-Pierre Dardenne, Luc Dardenne (Belgium/France)

The Dardenne brothers’ portrait of a disillusioned youth struggling after being abandoned by his father is an achievement that shouldn’t go unnoticed. Structured like a fairy tale but filmed in their usual gritty documentary style, the film is able to present it’s narrative that avoids sentimentality and cynicism. I’ve seen few films this year that are able to deliver as many emotional sequences, especially the final 20 minutes. The brothers also get one of the years best performances from young Thomas Doret.

9. A Dangerous Method – dir. David Cronenberg (UK/Germany/Canada/Switzerland/France)

It took two viewings for me to fully appreciate and understand the depth of Cronenberg’s newest film. Arguably the greatest genre director ever, Cronenberg takes on Masterpiece Theater/historical film, but in the usual Cronenberg fashion, ignores the genre’s usual trappings.stead his film’s drama alternates from intense debates of philosophy, psychology and dreams, all while hinting at the era’s prejudices and class differences (as well the eventual horrors to come from them). Following the triangle relationship between Carl Jung, Sigmund Freud and Sabina Spielrein, Cronenberg explores the birth of psychoanalysis. Understated and deeply personal, I imagine this is the film Cronenberg has been waiting his life to make and I’m glad hes the one to do it. In other hands, the film could either have been just another boring historical piece or one that was too interested in scandalous nature of the story.

8. Dreileben – dir. Christian Petzold, Dominik Graf, Christoph Hochhäusler (Germany)

I’m a little surprised that this ambitious film project didn’t get the attention it deserved, but then again maybe I shouldn’t be. The Berlin School has kinda gone unnoticed in the west but hopefully that will change, especially when you consider projects like Dreileben. Consisting of three films (Beats Being Dead/Etwas Besseres als den Tod; Don’t Follow Me Around/Komm mir nicht nach; One Minute of Darkness/Eine Minute Dunkel) by three of Germany’s most acclaimed filmmakers, the series presents three inter-locking stories tackling one terrifying incident with each director taking different angles. Its an interesting experimentation on narrative and is successful because each film stand alone representing different aesthetics and director trademarks. I’m not sure when or if this will reach the states but make sure to catch it hen it does.

7. Carnage – dir. Roman Polanski (France/Germany/Poland/Spain)

I’ve heard and understand the criticisms for Polanski’s Carnage and yet I don’t mind them. I wont go as far as putting this film above the Ghost Writer, the director’s incredible political thriller from 2010, but it does have an incredible charm reminiscent to his older work. Setting everything in an apartment, reminding us of the director’s accomplished Apartment trilogy as well as his 2010 house arrest, the film showcases the director’s greatest talents as well as those of his four stars. Telling the story of two New York couples meeting about a fight that took place between their two boys, we are shown the facades of each character slowly crack revealing their true natures. I can admit this probably isn’t as good as many of the director’s greatest achievements (I’d probably put this at the level of Death and the Maiden) but a minor Polanski is still better than 90% of what I saw this year.

6. Pina/Pina – Tanzt, tanzt sonst sind wir verloren – dir. Wim Wenders (Germany/France/UK)

Has anyone else been wondering what happened to Wim Wenders? The quality of work has dropped off substantially since the 80s and, unlike Werner Herzog (the only other active New German Cinema filmmaker) has had trouble staying relevant. I’m not sure where his newest film, Pina, stands among his best films yet but I can say it’s the first time I’ve actually been excited about a Wim Wenders film in a really long time. Wenders’ tribute to German dancer, choreographer and teacher Pina Bausch is equal parts documentary, musical and avant garde experimentation. Its a truly joyous work and Wenders follows the trend with recent film-making greats like Martin Scorsese, Werner Herzog, and Ken Jacobs to bring an artistic eye to 3D technology.

5. A Separation/Jodaeiye Nader az Simin – dir. Asghar Farhadi (Iran)

Winner of the top prize at the Berlin Film Festival, A Separation is easily the foreign film favorite this year ad for good reason. Its intelligently written, its well acted (Peyman Moaadi is fantastic as is the child actresses), and represents some of the strongest film direction in 2011. Descried by Farhadi as “a detective story without detectives,” he makes us the witnesses in a dilemma that has no right answers. There is a mystery in the story but what is emphasized are the characters and the problems in Iranian society. It works very similarly in the way that Nicolas Ray presents the crime in his 1950s masterpiece In a Lonely Place. And like that great film, A Separation is a truly emotionally draining. It’s also one of the best films I’ve seen in a while.

4. The Miners’ Hymns – dir. Bill Morrison (US/UK)

Bill Morrison may be one of the ten best American filmmakers working today and The Miners’ Hymns is proof of this. Using found-footage images of the mining communities of Northeast England, Morrison’s film spans decades, it’s at once a celebration and elegy to coal-mining culture in the city of Durham. Accompanied by a haunting score by Jóhann Jóhannsson, The Miners’ Hymns is a wonderful cinematic experience.

3. Once Upon a Time in Anatolia/Bir zamanlar Anadolu’da – dir. Nuri Bilge Ceylan (Turkey/Bosnia/Herzegovina)

This existential search for a dead body is one of the finest films I’ve seen this young century. Director Ceylan proves that he may be the heir apparent to Michelangelo Antonioni and his deconstruction of a police procedural provides more mysteries than it actually solves. This is a film that was made for multiple viewings and I plan to write a longer review later this month.

2. The Turin Horse/A torinói ló – dir. Bela Tarr (Hungary/France/Germany/Switzerland/US)

Bela Tarr’s swan song is his best film since his epic Sátántangó. In a year where many filmmakers filmed their own versios of the end of the world, Tarr’s apocalypse, or anti-genesis, trumps all. Following the final seven days of a father and daughter (and their horse), Tarr and his frequent collaborators, novelist László Krasznahorkai and partner Ágnes Hranitzky, create one of the most tragic portraits of a Godless world. The direction is pitch perfect, with one of the most haunting final shots ever. Few final films truly sum up a director’s career. Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Salo, Joris Ivens’ A Tale of the Wind, and Luis Buñuel’s That Obscure Object of Desire were able to achieve this. You can add The Turin Horse to that list.

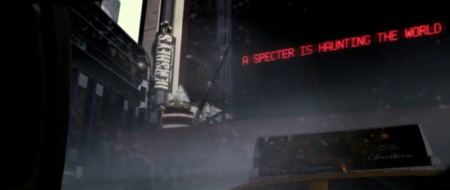

1. Tree of Life – dir. Terrence Malick (US)

Yes another end of the year list topped by Malick’s epic metaphysical and polarizing masterpiece. Comparisons to Kubrick’s 2001 are inescapable but really the greatness of Malick’s film is the coming of age story inside the grandiose art house experimentation. While I love the Malick’s version of the big bang, maybe the greatest cinematic interpretation of it since Brakhage’s Dog Star Man, the human story is the real draw. Hunter McCracken and Brad Pitt give two of the best performances of the year as the son and father. This ambitious project, one that has been years in the making, may be the greatest film Malick has ever made. Knowing hat, Tree of Life is nothing if not the movie of the year.